EPILOGUE

The fourth anniversary of V-J Day found the character of the Occupation changed through gradual evolution from the initial stern quality of a military operation to the friendly guidance of a protective force. Japan was well on the road toward becoming a sovereign nation once again. (Plate No. 95)

The Prime Minister spoke for his people in conceding progress toward economic recovery:1

In the economic field, we have started well on the road of stabilization .... Our budget is balanced. The administrative readjustment program is nearing completion .... the government is now engaged in the formulation of a plan for tax reform and tax reduction that will ensure equity and efficiency to our tax system ....

In pursuance of its economic stabilization policy the government will continue to strive to effect further retrenchment in expenditures. We intend to simplify and streamline our administrative machinery still further, while taking adequate measures for unemployment compensation and relief. We are vigorously pushing forward to promote enterprises, large and small, as a means of providing jobs to the unemployed, at the same time of enhancing the nation's economic power.

To that end it is imperative that we expand our export trade and import raw materials and technology as well as capital from abroad. We must also establish firmly law and order, assure the world of our social and industrial stability, and give proof of the soundness of our economic policy and practices... great deal has been accomplished-largely, however, with Allied assistance. But a great deal more remains yet to be done-done more by our own initiative and efforts.

In a parallel statement made on this same anniversary, General MacArthur summarized the progress of the Occupation and expressed his belief that Japan was ready to shoulder a major part of the responsibility for her recovery:2

Today marks the fourth anniversary of that historic event on the Battleship Missouri in Tokyo Bay when the warring nations of the Pacific entered into solemn covenants designed to restore the peace. The four years since passed have been fruitful years here in terms of human progress, as the Japanese people have fully and faithfully observed their surrender commitments and advanced steadily and progressively along the road of spiritual regeneration and physical reconstruction. Today Japan might, indeed, be viewed as a symbol of hope for less fortunate peoples overwhelmed by the despotic rule of coercive force. For, despite the continued presence on Japan's soil of an occupation force from beyond the seas, the Japanese people in their enjoyment of full personal freedom know that by their skill and their industry they serve no other cause but their own. They, themselves, plot the ultimate course of Japan's destiny within the family of free nations.

The past year has witnessed accelerated progress in every phase of Japan's reconstruction. True, as elsewhere, there have been assaults upon the integrity of the democratic process by the small existent Communist minority, but these assaults were effectively repulsed-not by the repressive force of police power but by the weight of an increasingly informed and active Japanese public opinion aroused to meet the threat to their free institutions. As a result, the threat of Communism as a major issue in Japanese life is past. It fell victim of its own excesses. The

[291]

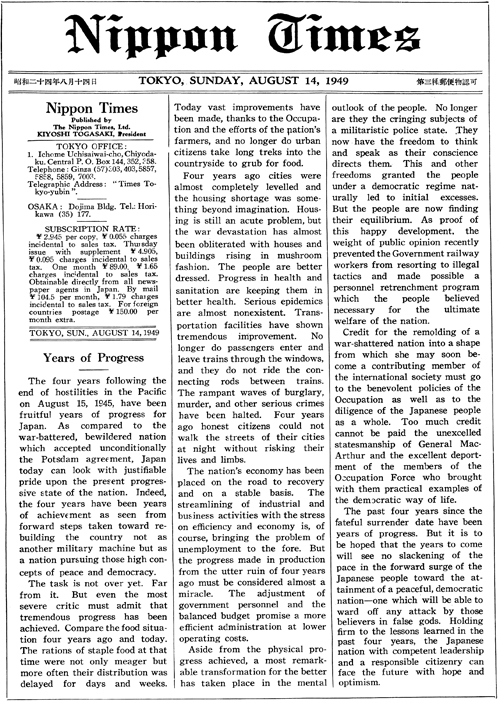

PLATE NO. 95

Japanese Newspaper Editorial Summarizes Four Years of Occupation, 1945-1949

[292]

Japanese mind penetrated the hypocrisy supporting its position. This test of strength, while disturbing to orderly progress, served to bring to light for the first time the full latent power of the Japanese devotion to the concepts of freedom and the integrity of their constitutional processes. Therein lies encouragement of Japan's potential strength as a bulwark of human freedom.

Politically, progressive gains have been made in the fabrication of a system of government truly representative in character. The lines of separation between the three great branches, executive, legislative and judicial, as provided by the constitutional design, have found strength in healthy public discussion of the vital issue of constitutional interpretation, and as a result the affairs of government have advanced with a minimum of overlapping friction and increasing inter-branch cooperation.

The development of the desired autonomous responsibility in the conduct of local affairs has been retarded somewhat by the need for rationalization in the field of government finance to permit local revenues to support local government. A remedy for this difficulty is now being evolved, providing hope that the coming year will produce the legal basis fully to sustain the severance of pre-existing centralized controls and support the development of a political and social system resting upon interrelated and self-sustaining segments at the community level from which the national government may draw its power and direction. Therein will lie the safeguard against the re-emergence of autocracy as the prevailing philosophy of government in Japan.

Probably the most significant political development of the past year has been the growing consciousness of individual responsibility in the conduct of public affairs. This has been given emphasis by a popular demand for higher standards of public morality, keynoted by action of the electorate in rejecting for return to elective office public officials whose public record was compromised by the exposure of corruption in government. Administrative and judicial action in the investigation of the stewardship of public responsibility and vigorous prosecution, without fear or favor, of violators of the public trust, not only have served to safeguard the public interest, but have given vital reality to the constitutional assurance of "equality before the law". There is thus rapidly taking form the ethical base upon which the pillars of a free, responsible and representative government safely may rest.

Socially, the Japanese people are wearing well their constitutional mantle of personal liberty and individual dignity. Apart from the growing consciousness of individual responsibility in the conduct of public affairs, there has been a sharp revulsion against persons who have failed to abide the law, with a resulting decisive drop in the incidence of private crime. The basic causes of social unrest throughout Asia have largely been eradicated in Japan by a redesign of the social structure to permit the equalization of individual opportunity and personal privilege. This is having a profound influence upon the economic potential, thereby fortifying the spirit against radical designs of either extreme to suppress freedom.

Substantial progress has been made in the building of an effective police system based upon the statutory principle of decentralization in the exercise of the police power. Increasingly the Japanese people are coming to understand that this power rests in their hands, rather than in the hands of any ruling clique, and provides the legal weapon for the preservation of the local security by their direction. They realize that the maintenance of internal order in the nation as a whole, subject to the safeguards provided by law, is dependent upon the manner in which each community administers the police power corresponding to its local responsibility. Here, too, difficulties are being experienced due to the present maladjustment of government finance, but this problem, as pointed out, is in process of solution. Apart from this, progressive strides have been made toward implementation of the new concepts embodied in the police law, and the police services are being administered with restraint, tolerance and commendable efficiency. The danger that a police state will re-emerge or that the police system as now constituted and manned will fail to maintain reasonable law and order is non-existent. Progress of trade unionization during the past year, despite a degree of freedom unsurpassed in modern civilization, has been somewhat impeded by the machinations of an irresponsible union leadership, but

[293]

its rank and file are showing an increasing awareness of this threat to labor's legitimate objectives and are moving to insist upon moderation and objectivity. Workers in the public service, through the functioning of a modernized and enlightened civil service system established by law, for the first time in Japan's history find protection of their rights and interests adequately provided for, without continuous struggle on their part, with machinery established for the hearing and adjudication of individual or collective grievances. This has resulted in a marked uplift in individual morale and greater attendant efficiency in the conduct of the affairs of government.

The enfranchised women of Japan are exerting an increasingly beneficial influence upon Japan's political, economic and social life. They are responding magnificently to the challenge of the attending responsibility and give every promise of proving a powerful and effective force in the shaping of Japan's peaceful destiny.

Economically, Japan is still in transition from an economy of survival to one of health, but the past year has witnessed significant progress along a broad front. Foremost of the gains made lies in the development of a more positive leadership and an increasingly informed public opinion.

Both leaders and people are coming to understand that representative democracy draws its strength from the support of a broad majority of the people imbued with the belief that under it they may attain a standard of living commensurate with the capabilities of modern civilization-that a prerequisite to that condition is individual freedom of activity in the field of economic enterprise, for no individual bound in economic thralldom can be politically free. Thus, for the vast majority of those who earn their living in industrial and commercial pursuits there could be no political freedom so long as their economic destiny was determined by decisions made in the closed councils of the few families which formerly controlled the vast bulk of the productive and financial resources of Japan. Nor could there be any political freedom for those who work the soil so long as they were economic serfs under a feudalistic system of land tenure. The fruition during the past year of the plans laid down by the Occupation and carried out by the Japanese Government to remove, through the Economic Deconcentration Program on the one hand and the Land Reform Program on the other, these barriers to the existence of a free society, has established in Japan the economic basis for the existence of a broad middle class which, having a stake in the economic well-being of the country, will support the ideal of democracy as their way of life and will reject with scorn any will-of-the-wisp economic utopias which require the surrender of the individual's freedom to the State.

With patience, fortitude and self-discipline the Japanese people withstood the privations of the immediate postwar period. With comparable energy, industry and hope they are now launched on the huge task of making Japan once again self-supporting among the family of nations. On the way to that goal great obstacles have been overcome, although some still remain. Since the summer of 1945, when productive activity in Japan was utterly paralyzed, the production of commodities and goods for home consumption, for industrial use and for export has risen steadily until now it is rapidly approaching the average level for the years 1930 to 1934, prescribed by the Far Eastern Commission as an interim standard. Coal, basic to so much of Japan's industry, is now being produced at a monthly rate of 3.2 million metric tons as contrasted with less than 1.7 million metric tons in 1946. Electric power, another basic ingredient of industrial activity, has attained a monthly volume of 3.2 billion KWH, as compared with 2.8 billion one year ago. Production of chemicals, necessary both for industrial uses and for the protection of the public health, has attained a volume of 105 % of the 1930-34 average, as compared with 76%, one year ago and 21% in January 1946. Equally significant advances have been made in other fields of economic activity, such as in the construction of dwellings and business buildings to replace those destroyed by war, and in the production of an increasing variety of goods both for home consumption and sale overseas.

To acquire the raw materials needed to feed her industrial machine as well as to overcome the deficit in her indigenous food production, Japan must export a large volume of goods and services. Despite

[294]

existing handicaps, chiefly the limited availability of raw materials from those sources which customarily supplied Japan in the prewar years, progress in this direction has been heartening. In 1946, Japan's total exports were $103,000,000-00; in 1947, $173,000,000.00; in 1948, $ 258,000,000.00, and in the first six months of 1949, exports had already exceeded the total for the full year 1948 by a sizeable margin.

In the past twelve months two significant decisions to promote the economic rehabilitation of Japan were taken by the Government of the United States. One was that of May 1949, to cease the removal of industrial plants for reparations. This action dispelled the pall of uncertainty which had previously paralyzed entrepreneurial initiative and restored the incentive to the investment of capital in the rehabilitation and construction of capital plant and equipment. The second was the authorization by the Congress of the United States of limited budgetary appropriations for financing the importation into Japan of materials needed for rehabilitation purposes in addition to the appropriations previously made for the importation of primary necessities such as food, fertilizer and medicines to protect the Japanese people against widespread suffering and disease.3

The enactment by the Japanese National Diet in the spring of 1949 of a national budget which for the first time in many years achieved a true balance, and subsequent action to sharply curtail the cost of government by streamlining its structure and reducing its personnel, have struck at one of the contributing factors in the postwar inflation and are gradually effecting greater stability. To prevent the specter of inflation from rising again, a firm and determined course based upon sound fiscal and financial policies is now being pursued by the Japanese Government. This, accompanied by maximum utilization of indigenous resources and efficient employment of the manpower of Japan in the useful pursuits of peace, will speed the day when the Japanese economy will be stabilized and its dependence on American subsidy eliminated.

To stimulate productive endeavor and to strengthen the foundations for the growth of free private competitive enterprise in Japan, the economic controls necessitated by the war-generated shortages of critical materials have been removed as fast as the availability of adequate supplies has obviated their necessity. The timing of progressive further relaxations will, of course, depend on the progress of the transition from an economy of scarcity to one of normalcy.

Since October 1, 1945, nine and one-half million people have been added to the population of Japan-five million by repatriation and the rest

[295]

through natural increase. Yet there has been no mass unemployment, no social unrest and no large-scale dole. In June 1949, persons reported as totally unemployed were fewer than 400,000. Further, despite recent reductions in the number of government employees in the interest of governmental economy and efficiency and the current rationalization of industry necessitated by the adoption of a single foreign exchange rate for foreign trade and the transition from subsidized to competitive industry, total unemployment by the end of August 1949 is estimated not to exceed one-half million persons. During the twelve months ended June 30, 1949, the total number of persons at work in any given week averaged over 34.5 million, as compared with 32.9 million in the preceding twelve-month period, or an average increase of 1.6 million in the total number of persons at work. In June 1949, the total number of persons at work stood at an all-time high of 37.4 million. These figures reflect an orderly absorption of the working energies of the increasing population in an expanding number of employment opportunities in industry, agriculture and small scale family enterprises. Unemployment, therefore, presents no major problem at the present time, and the expanding areas of employment in the work of reconstruction will stand safeguard against any acute unemployment problem in the foreseeable future.

Since the full employment of Japan's industrial potential requires a vigorous revival of her foreign trade and since among her chief customers in the past were the countries bordering on the Pacific basin, the question as to whether Japan will regain her traditional trade with China, despite the stranglehold of Communism upon that tragic land, has been mooted with increasing frequency. This question is largely academic. Foreign trade requires production in excess of domestic needs. Human experience demonstrates with striking clarity that the further removed a people become from the economic philosophy of free enterprise in like ratio does its productive capacity deteriorate. This deterioration proceeds until, as under Communism, with incentive completely lost, the human energy and individual initiative which find their expression in production give way to indolence and despair. In such unhealthy climate

industry and commerce cannot thrive and realism warns that the potentialities of trade with any people under the strictures of a collectivistic system must be discounted accordingly. For the time being, therefore, and for some time to come, Japan must look elsewhere for the sources of her needed imports and the markets for her manufactures. Against this need Japan has already initiated foreign trade with 113 other countries and territorial areas.

I dare say that no operation in history has been subject to such extraordinary divergence of opinion carried in the media of public expression than has Occupation of Japan. Some writers have been extravagant in their praise, others no less extravagant in their criticism. The truth, awaiting the judgment of history, will rest somewhere in between.

Nor has there been any operation subject to such a variety of influences and pressures-the ideological protagonists, the special pleaders, the vindictive and the lenient-many seeking to influence public opinion through prevarication of the truth. In the search for sensationalism, incidents in Japan, elsewhere scarcely worth the public notice, have been exaggerated out of all proportion to their true significance, with the serenity and order and sincerity of purpose normal to postwar Japan all but ignored. And time and again simultaneous attack has been leveled against Occupation policy, by the leftists as too reactionary and by the conservatives as too liberal. Such an atmosphere, while giving assurance that our moderate course is well charted, does not contribute to an objective public appraisal of the situation.

The great and noble effort by the American people, with the wholehearted support of other Allies, toward the reorientation and reconstruction of postwar Japan, beyond peradventure of doubt, will prove eminently successful. Long hence history will record of the Occupation that its greatest contribution to the progress of civilization was to introduce into Japan the great concepts of personal liberty and individual dignity and to give the Christian ideal the opportunity to advance into Asia.

Of the Japanese people I can pay no higher tribute than to repeat that they have fully and faithfully fulfilled their surrender commitments and

[296]

have well earned the freedom and dignity and opportunity which alone can come with the restoration of a formal Peace.

In a previous message to the people of Japan on the second anniversary of their new constitution the General had forecast the future in a policy of progressive emancipation:4

While insisting upon the firm adherence to the course delineated by existing Allied policy and directive, it is my purpose to continue to advance this transition just as rapidly as you are able to assume the attending autonomous responsibility. Thus progressive latitude will come to you in the stewardship of your own affairs.

One of the most important elements in relaxation of controls was a plan for the gradual deactivation of forty-seven prefectural civil affairs teams,5 culminating in the absorption of their duties and responsibilities by only seven regional and the Hokkaido (District) civil affairs teams, announced by GHQ, SCAP, on 28 July 1949. The remaining teams were to be maintained at approximately their former strengths but were to be staffed primarily by civilians trained in economics, education, welfare or some other of the civil affairs departments, with a minimum number of military personnel for administrative purposes. The plan further provided for the discontinuance of the Civil Affairs Section of Eighth Army and the establishment of a small Civil Affairs Section in GHQ, SCAP; the transition was to be completed by 31 December 1949.6

This progressive relaxation of controls was designed to permit the local Japanese officials to assume more and more responsibilities in their respective fields as rapidly as they demonstrated their capacity to undertake them.7

[297]

Go to

Chapter IX

Last updated 11 December 2006 |